Towards a More Democratic Health System: Reflecting on the Alma-Ata Declaration

This article delves into the landmark Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978, highlighting its pioneering vision for global health and the significance of primary health care. While acknowledging the Declaration's foundational principles, the piece also underscores the challenges and gaps in its interpretation and implementation. Emphasizing the need for community engagement, interdisciplinary approaches, and addressing systemic barriers, the article advocates for a more inclusive and democratic health system that truly embodies 'Health for All.

SOCIAL MEDICINE

10/14/20232 min read

Towards a More Democratic Health System: Reflecting on the Alma-Ata Declaration

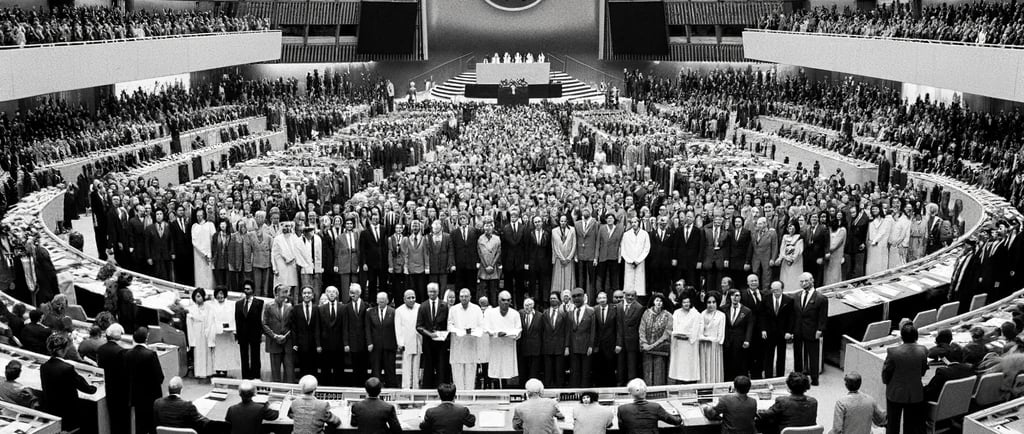

The Alma-Ata Declaration, signed in 1978, showcased a pioneering shift in global health perspectives. Recognizing health as an all-encompassing entity intertwined with socio-economic development, the Declaration emphasized the significance of primary health care in achieving the goal of Health for All (World Health Organization, 1978).

The Alma-Ata’s Vision and the Missing Links

While the Alma-Ata's vision was groundbreaking, there have been notable gaps in its implementation and interpretation:

Systemic International Structural Barriers: The document alluded to, but did not comprehensively address, the deep-rooted impacts of colonialism and the commodification of healthcare by the medical industrial complex (Navarro, V. 2007).

Primary Level Care vs. PHC: The nuanced differences and connections between these two concepts remain inadequately elaborated, leading to potential misinterpretations.

Irrational Use of Technologies: While the Declaration emphasized appropriate technology for primary care, it often overlooked the challenges posed by over-reliance on high-end technologies that may not always serve the best interests of the community.

Power Dynamics of Medical Professionals: The continued dominance of biomedicine and the medical profession was not addressed in-depth, leading to an imbalance of power in healthcare systems (McKee, M., Stuckler, D., & Basu, S. 2012).

Ethical Concerns: Issues like corruption, iatrogenesis, and the ethics of health services were largely overlooked.

Community Understandings: The Declaration sometimes romanticized the notion of "community," overlooking the complexities within, including differences related to gender, race, and class.

Epistemic Pluralism: The recognition and integration of diverse forms of knowledge, beyond just modern medicine, were not given adequate attention.

Transforming Health Systems for the Marginalized

To create a health system that truly serves everyone, particularly marginalized communities, several transformations are necessary:

Community Engagement: It is pivotal to understand and engage communities in decision-making processes, reflecting their needs, knowledge, and experiences.

Interdisciplinary Approaches: Combining political economy with the politics of knowledge offers a comprehensive understanding of the health system's workings (Farmer, P. 2005).

Addressing Hierarchies: Both in healthcare education and service delivery, there is a need to flatten hierarchies to foster teamwork, mutual respect, and patient-centered care.

Incorporating Traditional Medicine: Traditional medicine systems should be acknowledged for their value. Research should be undertaken to validate and integrate these systems within mainstream healthcare.

Women's Health: The health needs of women, transcending biological vulnerabilities, must be prioritized and understood within socio-cultural contexts (Sen, G., Östlin, P., & George, A. 2007).

Conclusion

While the Alma-Ata Declaration laid a foundational vision for global health, its interpretation and implementation need revisiting. A democratic health system is one where community engagement, interdisciplinarity, and power dynamics are thoroughly addressed, and where the true essence of Health for All is realized.

References:

World Health Organization. (1978). Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care.

Navarro, V. (2007). What we mean by social determinants of health. Global Health Promotion, 14(1), 5-16.

McKee, M., Stuckler, D., & Basu, S. (2012). Where there is no health research: what can be done to fill the global gaps in health research? PloS Medicine, 9(4), e1001209.

Farmer, P. (2005). Pathologies of power: health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. University of California Press.

Sen, G., Östlin, P., & George, A. (2007). Unequal, unfair, ineffective and inefficient. Gender inequity in health: Why it exists and how we can change it. Final report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health.